Recently, an almost unbelievable news story from Hong Kong popped up in my newsfeed—a scam group used deepfake technology to impersonate a senior executive of a large corporation, tricking an unsuspecting financial officer into transferring a whopping $25 million! This incident, straight out of a sci-fi novel, has become a reality. It exposes the potential dangers of deepfake technology and forces us to reevaluate the safety and ethical boundaries of artificial intelligence (AI) technology.

Fortunately, efforts to address these concerns are well underway, with the European Parliament passing the European Union Artificial Intelligence Act and showing the world that regulation of AI is a must rather than a nice-to-have. This historic document aims to regulate the safe use of AI systems, marking a significant step towards ensuring technological innovation does not compromise public safety and rights. But what is the AI Act all about, and what does it mean for us here in New Zealand? This blog post sheds some light.

Artificial intelligence is already very much part of our daily lives. Now, it will be part of our legislation too.

Roberta Metsola, President of the European Parliament

What is the EU AI Act?

In simple terms, the Act defines an artificial intelligence system and categorises AI applications based on their risk level. All AI systems sold or used in the European (EU) market must comply with this Act. Moreover, the scope of this legislation extends beyond the EU, encompassing any AI system that impacts the EU.

For New Zealand’s AI developers and providers, this means that if their systems come into contact with the lives of EU citizens – whether through online services or handling their data – they may fall under the jurisdiction of the Act. Kiwi tech pioneers must weave EU compliance into their digital strategies. A free EU AI Act Compliance Checker can help New Zealand-based AI developers and providers determine if their AI system will be subject to the obligations of the EU AI Act.

Classification and Regulation of AI systems

The legislation has classified AI systems into four categories based on their potential impact on users and society: unacceptable risk, high risk, limited risk, and minimal risk.

Each category has its own set of regulatory requirements. High-risk AI systems must comply with stricter rules, while AI systems that pose an unacceptable risk are banned entirely, as shown below.

AI systems that are capable of manipulation, deception, exploitation of vulnerable groups, improper categorisation, and facial recognition databases created through indiscriminate scraping of images from the internet or CCTV and “real-time” Remote Biometric Identification (RBI), unless used for searching for missing or exploited persons, preventing life-threatening situations or terrorist attacks, and identifying serious crime suspects.

Example: Social scoring systems and manipulative AI.

Regulation: Prohibited.

AI systems that pose a significant risk of harm to the health, safety, or fundamental rights of natural

persons in the areas of critical infrastructure, education, employment, essential services, law enforcement, migration, and administration of justice and democratic processes.

Example: CV-sorting software for recruitment procedures.

Regulation: Regulated, all enterprises using high-risk artificial intelligence systems must fulfil extensive obligations, including meeting specific requirements related to transparency, data quality, record-keeping, human oversight, and robustness.

Before entering the market, they must also undergo conformity assessments to demonstrate their compliance with the Act’s requirements.

AI systems that are considered to pose no serious threat. Their main associated risk is a lack of transparency.

Example: Chatbots and deepfakes.

Regulation: Limited regulated. Subject to lighter transparency obligations: developers and deployers must ensure that end-users are aware that they are interacting with AI.

The Tesla Autopilot case demonstrates the importance of developers and deployers ensuring that end-users are aware they are interacting with AI systems, as misunderstandings of its capabilities can lead to severe consequences.

The majority of AI systems in use in the EU fall into this category.

Example: AI-enabled video games and spam filters.

Regulation: Unregulated.

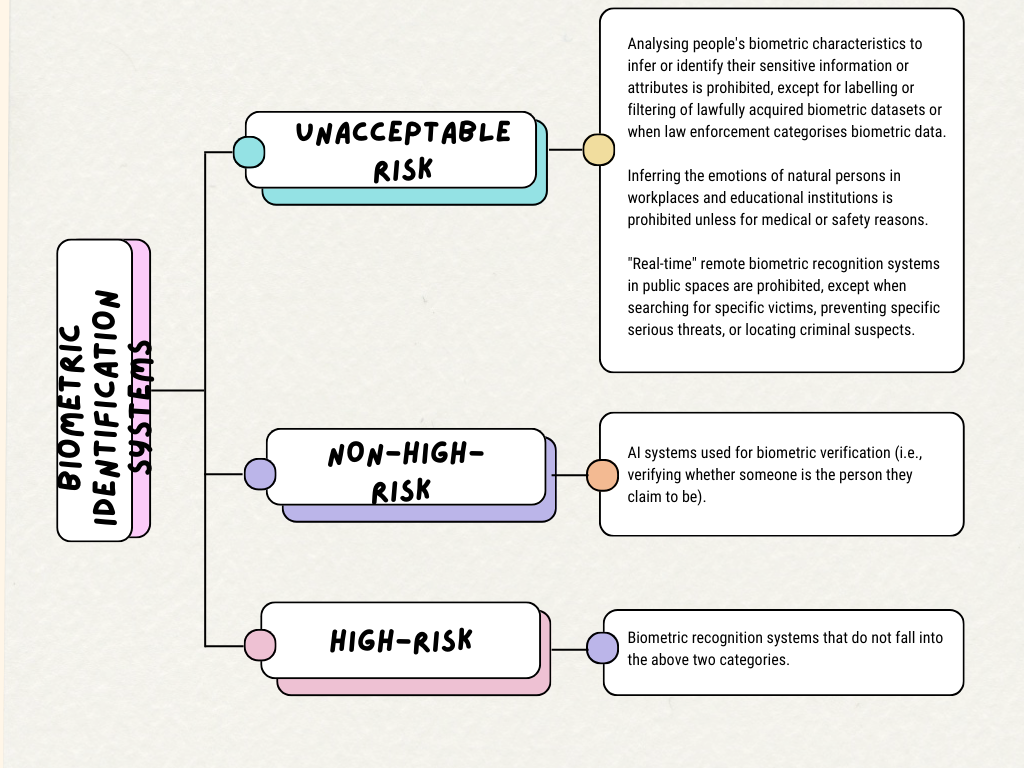

As we proceed from discussing AI system risk classifications, we must mention another critical component: biometric identification systems.

Although the EU AI Act does not classify those systems as AI, their use is regulated within the framework of AI systems. Still, various definitions and approaches exist across the European Parliament, the European Commission and the Council of the European Union, making it tricky to interpret accurately.

Biometric identification systems blend advanced technology with our personal data, raising privacy and ethical questions. It is crucial to understand which biometric identification systems are permitted and which are prohibited. The classification information is laid out in the diagram below.

Potential Penalties for Violations against the EU AI Act

The European Union Artificial Intelligence Act sets different levels of penalties based on the nature of the violation:

Directly violate prohibitive AI practices.

Violate provisions of the Act other than prohibitive AI.

Providing incorrect, incomplete, or misleading information to the regulatory authority.

The Road Ahead: Navigating the Complexities of the EU AI Act

The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act is a beacon of hope for the responsible use of AI, guiding us toward a future where technology serves humanity without compromising our safety or ethical standards. However, the journey toward this ideal is fraught with known and unforeseen challenges.

The Gray Areas of AI Regulation

One of the most significant hurdles we face in implementing the EU AI Act is the ambiguity surrounding the boundaries of AI applications, especially when it comes to personalised recommendation systems. At what point does personalised guidance become an infringement on individual autonomy? This question is not just technical but deeply philosophical, touching on varying perceptions of manipulation and ethical persuasion across different cultures. What one culture might see as a legitimate marketing strategy, another could view as unethical manipulation. This cultural diversity, while enriching, complicates the regulatory landscape, making it challenging to draw clear lines in the AI sand.

Balancing Innovation with Regulation

Another pivotal concern is how to foster a safe, ethical, and transparent AI ecosystem without stifling the spirit of innovation and investment vitality. The EU AI Act, with its focus on governance, compliance costs, and requirements for data and algorithm sharing, inadvertently adds a financial burden on businesses, particularly start-ups and small to medium businesses (SMBs), in addition to potential fines for noncompliance, they must also, for example, bear the upfront costs of ensuring adherence to regulations, including data and algorithm transparency, record-keeping, and human oversight. These entities are the lifeblood of innovation and competitiveness in the digital economy, and overregulation risks dampening their entrepreneurial spirit, potentially slowing down Europe’s growth and technological leadership in the digital age.

Moreover, potential risks to intellectual property and concerns over regulatory access to data could further deter private sector investment, creating a cautious environment that is less conducive to bold, innovative ventures.

Navigating AI Regulation: The Impact of the EU AI Act on New Zealand’s Tech Industry

As the European Union introduces an unprecedented Artificial Intelligence Act, one might wonder how other countries fare in this area. The global response varies widely, but there is a shared recognition of the need to regulate AI technologies.

This week, the New Zealand Privacy Commission launched an investigation into using facial recognition technology in 25 Foodstuffs stores to ensure compliance with privacy laws. Meanwhile, due to privacy and data usage concerns, the US Congress has temporarily halted a significant AI service, Microsoft Copilot. These instances highlight a growing global concern about AI governance.

Looking back at New Zealand, we find that, despite global efforts to promote responsible AI usage and governance, the country faces legislative gaps in addressing specific AI systems such as deepfakes. The current legal frameworks fall short of adequately addressing the complex challenges presented by this emerging technology. The lack of or insufficient laws and regulations is not a unique issue for New Zealand; many countries worldwide struggle with this problem. Therefore, ensuring that AI technology benefits humanity rather than poses a threat has become a central issue in the global regulation of AI.

How do we take action? How do we responsibly use AI technology to serve humanity rather than AI becoming a threat to our people? Should New Zealand adopt the EU’s AI Act or forge its own path? What do you think? We welcome your comments.